Etymological Digression

THE SHORTEST DISTANCE BETWEEN A AND B is a straight line. But the trip is often dull. Granted that a scientific paper should make a bee-line from “If we accelerate atomic particles magnetically to near-cvelocity…” to “QED [See appendix for charts].” No stops at the tavern, no sidelights on the lab’s bill for liquid nitrogen, or how a forgotten screwdriver was magnetically accelerated to a homicidal velocity that nearly punctured Dr. Moyes.

The dedicated purpose of Dockwalloping is to follow the path of maritime language to its acceptance as slang ashore. Inherently interesting. But if we stray, branches on the trail often drop my jaw, “Golly!” Thus it is with the well-known term scuttlebutt, understood to mean gossip, general rumor, speculation on what may come, who struck John, &c. Why?

The explanation’s bones are simple. Barrels were made in many standard sizes. The little firkin holds only 8 US gallons (30 litres). The tun customarily used to age wine holds 252 US gallons (954 litres). The butt holding 126 US gallons (477 litres) was the preferred choice to store water, tons of it, stacked and securely chocked in the lower decks of a sailing vessel. An excellent marine verb is to scuttle, which means “to bore holes, to open.” You scuttle a ship by boring holes in the hull, glub, glub. A butt lashed to an aft mast on the gun deck was the fresh water supply for sailors. It was open – probably with a lid of some kind to discourage salt spray and detritus – so it was “scuttled.” Sailors stepping aft to refresh themselves met other sailors and, in the time-honored tradition of the sea, shared stories both tall – “Now this ain’t no shit,” – and commonplace – “Chips was tellin’ the gunner that we’re Boston bound.” Sharing bits of data in varying shades of accuracy comes naturally in a seasoned crew. Being exposed to these tales by the scuttled butt gave data-sharing a name for ship’s gossip: scuttlebutt.

Now we embark on our first digression. We can’t help it! Because one of civilization’s oldest and most useful engineering achievements is the barrel.

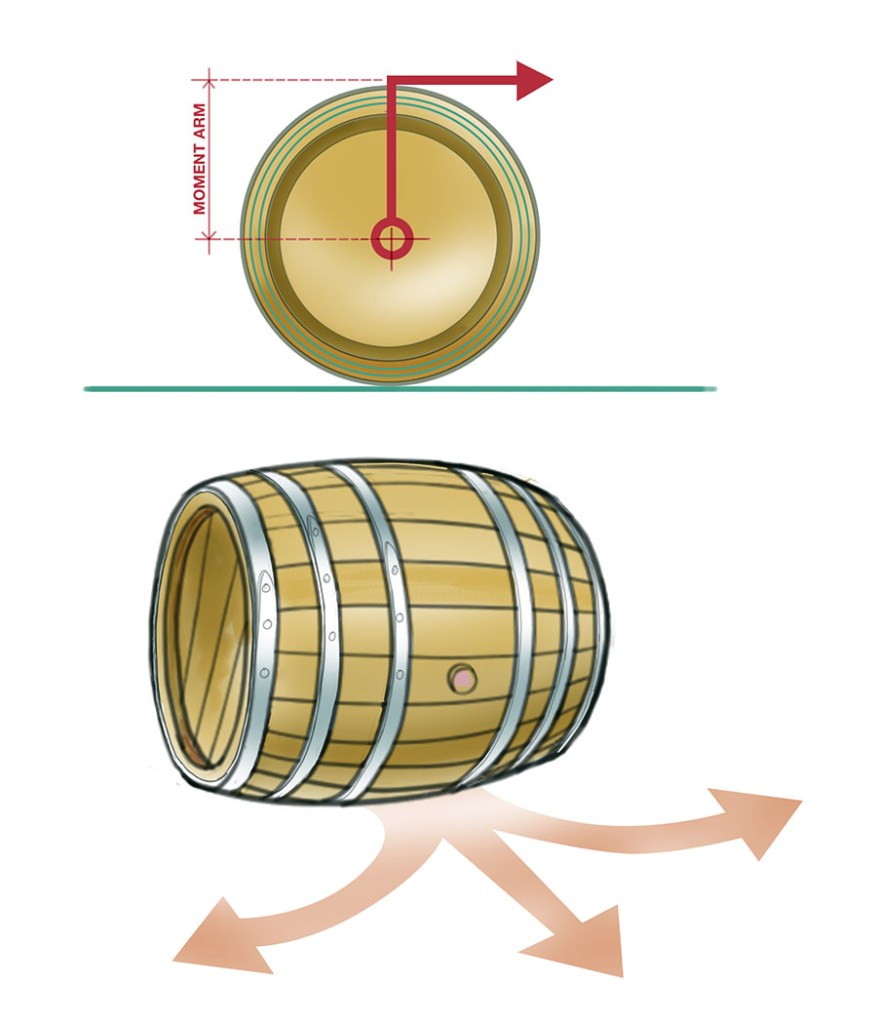

That 126 gallon butt of fresh water weighs about 1100 pounds (~500 k) but on a plank dock or a smooth-paved quay, one man could move it along at a walk and maneuver it smartly because the barrel is a brilliant piece of technology. Little of the barrel rests on the ground because its solid geometry presents a shallow arch all around (this arch also accounts for its strength). The barrel rolls and turns easily. A barrel roller pushes the upper tangent of the arch, giving him a mechanical advantage of half the barrel’s diameter.

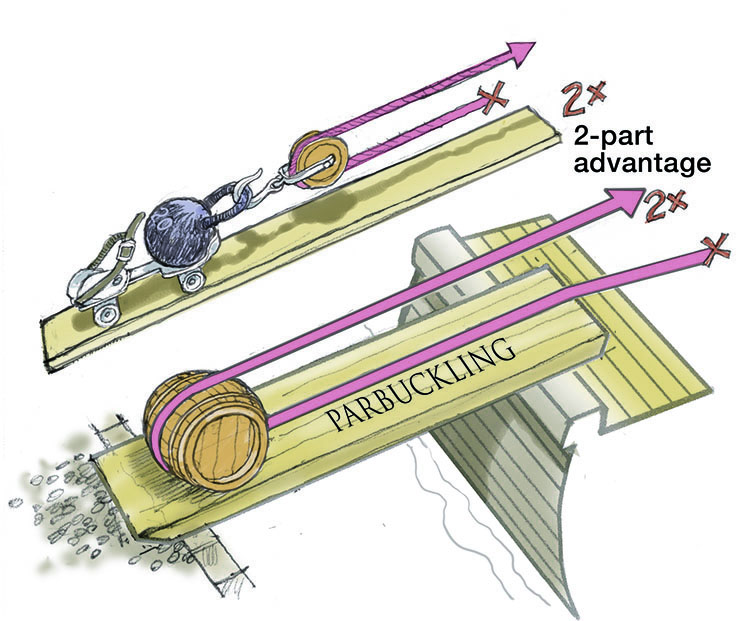

Another advantage to the barrel roller is using the round barrel, itself, as the sheave in a block-and-tackle rigged to advantage (arranged to increase the strength of the pull). In the upper illustration we place a weight on an old-style roller skate, attaching it to a block (proper sea-term for a pulley), from which both lines lead toward the puller. One line is cleated, the other is pulled, and the puller gains a two-part advantage, pulling half the roller skate’s load. In the image below, a barrel is being drawn up a gangplank to the deck. The rolling barrel, itself, acts as its own turning block. The lower strap is made fast on dec, and the upper strap is pulled. This gives an advantage of 2X: the puller uses half the effort of rolling the barrel upward. This ancient arrangement (more often managed with two separate lines) is called parbuckling.

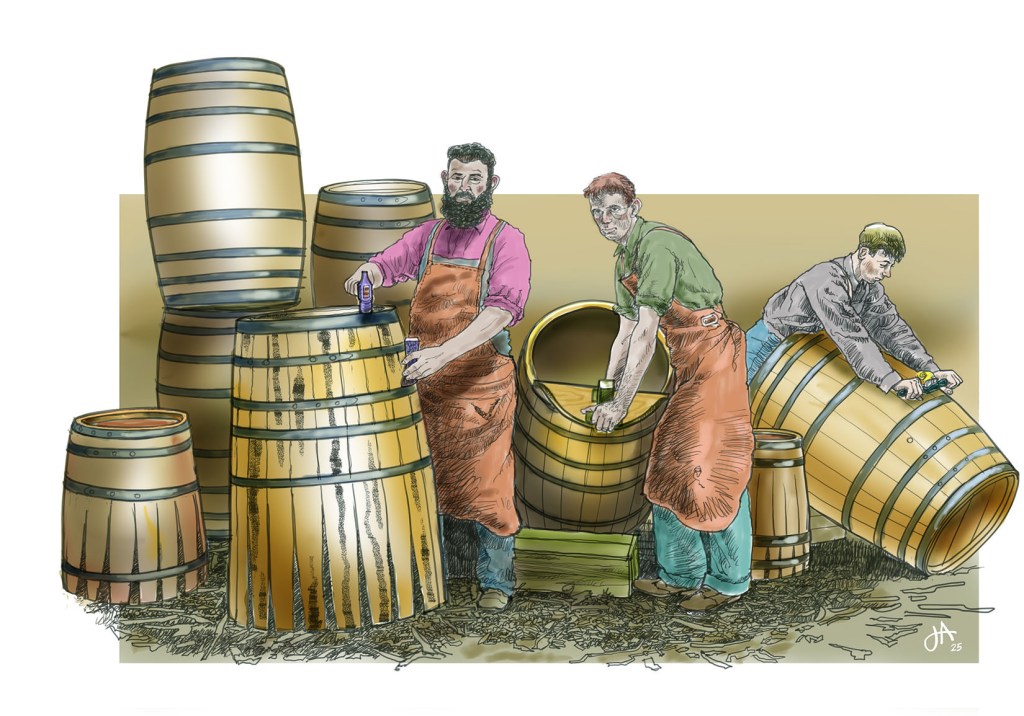

This barrel’s exterior arch is shaped from identical, tightly fitted oak staves mortised at the ends – forming the circular chime furrow – to accept a chamfered barrelhead of tightly joined flat oak planks (pinned side to side with dowels, fiber filler between them). Even a small ship might sail with hundreds of barrels holding . . . everything: ships biscuit, dried peas, salt, raisins, salt pork and beef, lemon juice, and even crockery. In the last Dockwalloping blog we saw Admiral Nelson conveyed home tightly barreled in alcohol and myrrh.

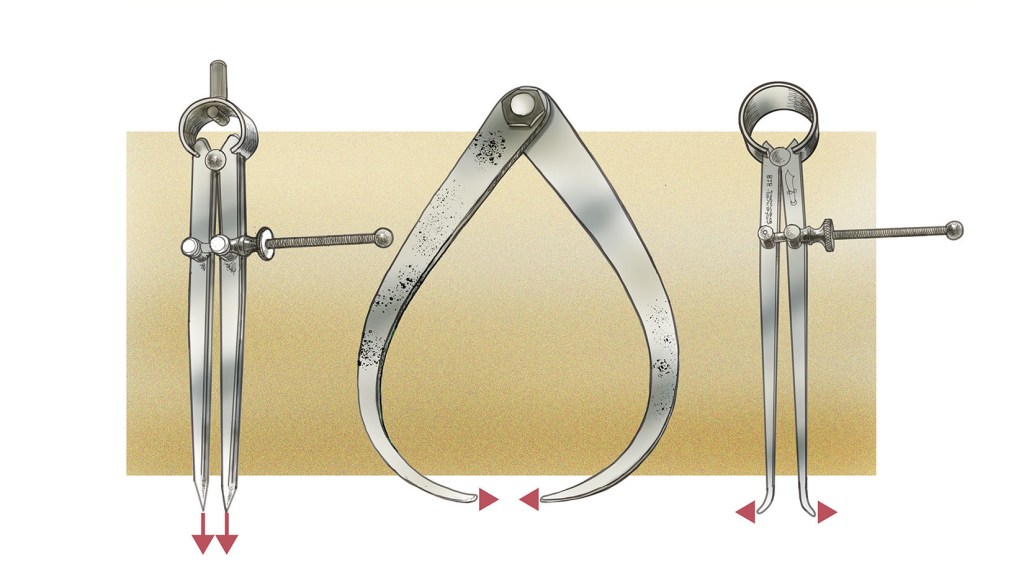

The centrifugal force of the rolling barrel – the content weight bearing outward – is countered by six or seven metal barrel hoops, tightened against the sloping barrel sides with a maul and a curved hoop driver. (You can see the maul and driver being used by the big fellah in the illustration of coopers. )

A ship would also carry barrel kits called shooks – all the staves and head-planks bound in a tight bundle ready to assemble. The hoops would be gathered in groups of six or seven with twine. Every ship of size carried a cooper, to tend, make, and repair barrels. The cooperage trade was exacting, requiring long apprenticeships and specialized tools to shape and join the staves and heads precisely. On a whaling ship, the cooper received an especially handsome plank-share, since the precious whale oil was carried home in his (hopefully) tight barrels put together from shooks.

Coopers were essential to life aboard. Consider the butts of drinking water. Of more immediate concern to the jacks were the smaller barrels of tobacco, and the casks of naval rum. The physics of the barrel is forgotten now in the growl of hoist engines and a hundred varieties of watertight plastic and steel containers, though the barrel’s importance in pre-industrial life was immense.

But now we make our second digression: water at the scuttlebutt.

Whence? Where did that water come from? The best water would be from hillside springs, naturally filterd by rock and gravel. But water, to a captain or ships surgeon in the early 1800’s, was water. It would be taken from any “fresh” (non-salt) source – a brook, stream, creek, river. Any place along a foreign shore where fresh water could be sourced close to a landing place for ship’s boats.

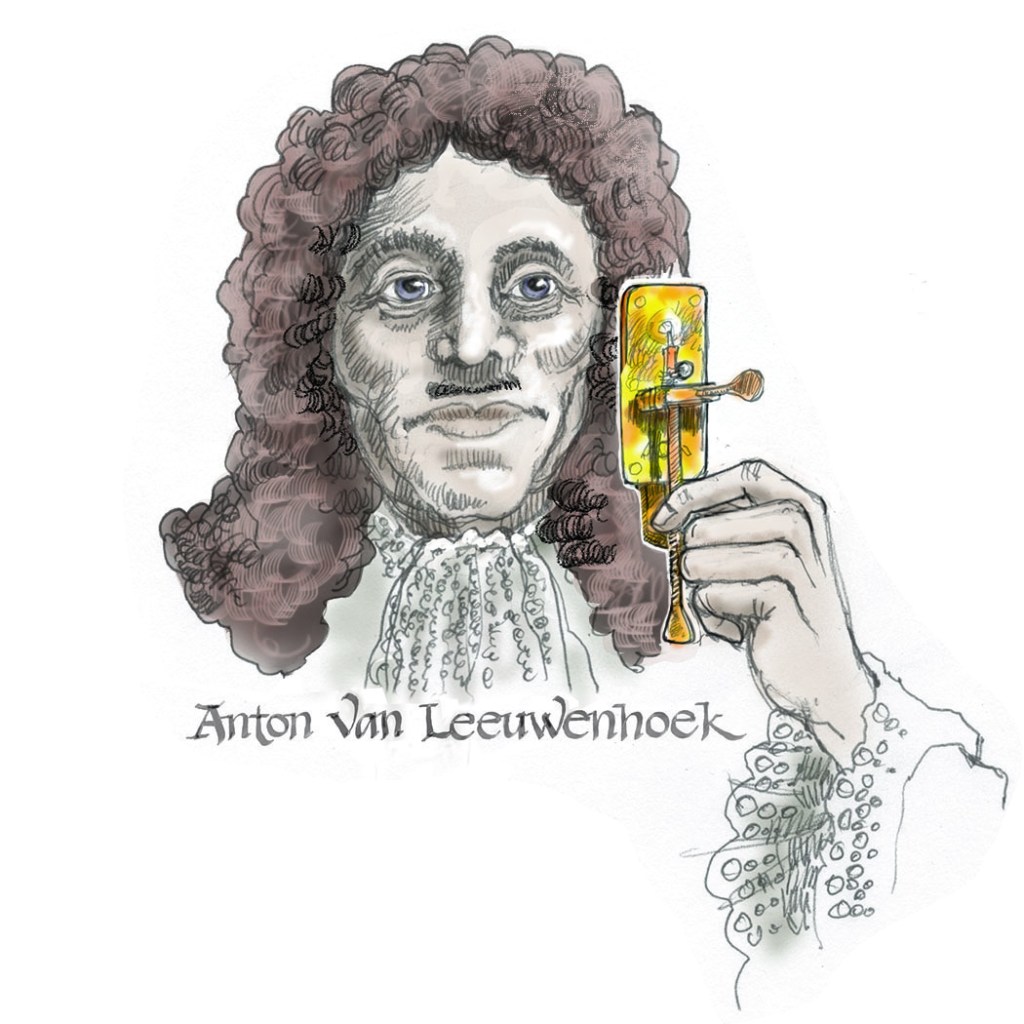

In the late 1700’s Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Dutch fabric merchant, began to experiment with tiny lenses, the first microscopes, and was astonished to discover miniscule animals invisible to the naked eye, wriggling and propelling themselves through local water. He called these creatures animalculae and became the father of modern microscopy. The little critters were interesting but there was no way to know what they did or how drinking water full of them might affect Jack Tar.

And there were plenty of them, everywhere. Put potable tap water into an oak barrel and store it for a couple of months in the dark. When you scuttle this butt the water will be green and stink. Only sterile water contained in a non-porous, sterilized vessel will be drinkable. When barrels filled with pond or stream water were opened after months it was not unusual to find tadpoles and other aquatic critters. By our hygienic standards the drinking water brought up in butts was abhorrent.

But what were the hygienic standard aboard a Napoleonic War man-o-war? You wouldn’t have liked them. In many crucial ways the common theories of infection, disease, epidemiology, nutrition, and health were stunted by faith in an ancient set of assumptions made by early Greek “physicians” like Galen and Hippocrates. Their conclusions were that bodily health was due to the balance of four humors (fluids) in the body: black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm. The ancient Greeks and – more than a thousand years later – 19th century doctors tried to make medicine scientifically understandable by gauging cause and effect in relation to the “balance” of the four fluids. “Bleeding” a patient – using a special knife called a fleam – was a hopeless attempt to restore the humoral balance. We suspect that the ailing George Washington died early from frequent bloodletting that sapped his strength.

What is astonishing to modern medicine is the absence of empirical data, the lack of scientific rigor well-established in many other sciences. Leeuwenhoek was ultimately able to see many microbodies but there was no connection between animalculae and disease. The process of infection was supposed to come from humor imbalance and from “foul air,’ smells of various nasty kinds. To this day one of our dreaded diseases is called malaria, which translates to “bad air.” To prevent infection during the Great Plague years, physicians wore strange bird-like leather head-dresses with goggles; the “bird” beaks were stuffed with flowers! Medicine was in some ways crippled by faith in the ancient idea of humors, a progress was slow. It appalls us that during our Civil War surgeons north and south stropped their surgical instruments on their boot soles.

In many ways an ailing patient had a stronger chance of recovery if treated by isolated country herbologists. The effects of country herbs were empirically established and not confused by black and yellow bile. Willow bark was a good pain reliever. Aloe soothed burns. Ginger soothed nausea. The sad truth is that Jack Tar had a high death rate due to simple diseases that could have been avoided by basic hygiene. Only 10% of sailor death during the Napoleonic wars due to battle; the rest died of diseases like scurvy, typhus, dysentery, malaria, and simple infections. The ship’s surgeon had a full medicine chest of many potions and notions but very few had benign effects. The most powerful pill the surgeon could offer was the placebo.

It’s likely that bad drinking water harmed Jack’s health. There was a healthier drink: beer. Small beerwas commonly provided, when available, at one gallon per man per day. At 1% to 4% alcohol by volume, it was not enthusiastically inebriating (modern beer is usual 4% to 5% ABV) but it was remarkably pure; this is due to the victory of yeast over bacteria in beer brewing, the fact that many breweries filtered their water with sand and charcoal, and the basic boiling water stewing of the beer mash wort made a healthy beverage from the tap or from hot-poured barrels.

Beer quenched thirst. Rum was meant to relax the watch off-deck and was a fiercely respected privilege. The rum ration, along with the tobacco ration, may have been one of few blandishments to join the Royal Navy. Long ago, the ration was stiffer – up to a half-pint a day of 54.6% ABV (95.5 proof) Royal Navy rum (made as a monopoly in RN distilleries). The ration sank to about 2 ounces of rum mixed in fanatical precision with water, sugar, and lemon juice (anti-scurvy, a leap forward in health) to make grog. It’s not a bad tope, and it sustained the Royal Navy until Black Tot Day, July 31st, 1970, when the last grog was issued in Royal Navy vessels.

Was 2 ounces of rum enough to “disinfect” bad water? Probably not, and it certainly wouldn’t discourage some dangerously hardy microorganisms. Was butt-water aboardship any worse than water in the big cities? No. Massive epidemics of many water-borne infections raged across cities everywhere. The mechanism of microorganisms and the advantages of sterile water simply wasn’t given credit. Vaccinations for some diseases like smallpox had begun in the late 18th century but too little was understood about the vectors of disease.

But water with tadpoles?

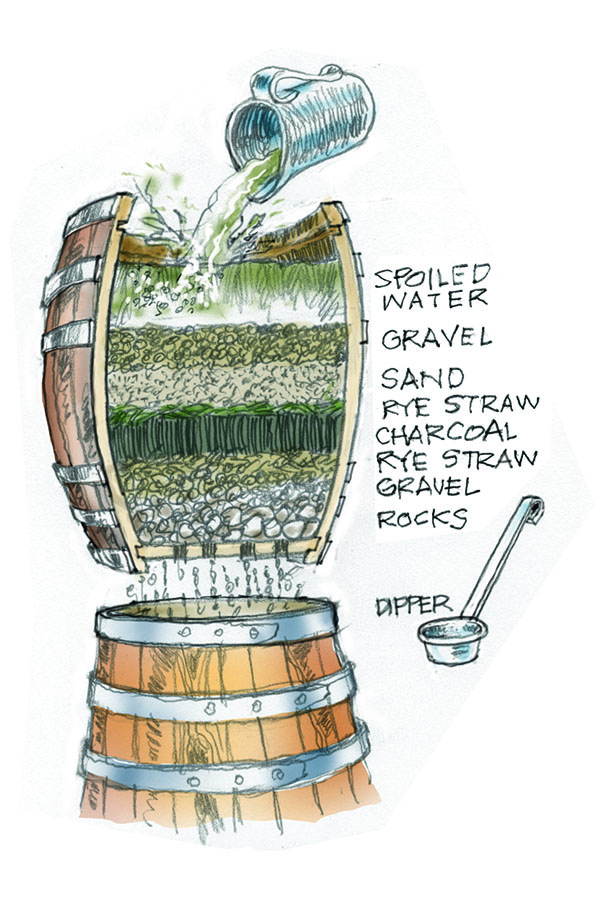

I find no research for filtration aboard ships, which is odd because it’s a simple and nearly complete solution. Filtration technique was in wide use ashore. Ancient Pharaohs used efficient water filters to clear the water of the Nile. The Royal Navy actually had water distilling stills but these used excessive amounts of wood or coal (at a premium, afloat) to boil the water for a paltry volume of clear and poor tasting water. A simple scuttled barrel (holes in the bottom) partially filled with layers of filtration materiel, as shown, would produce large quantities of water free of tadpoles and nearly all malignant microorganisms. Hindsight 20/20? Or, since filtration was culturally accepted for thousands of years, was it merely that the customs and procedures at sea didn’t embrace fripperies like clean drinking water? I’ve reached a dead end to this digression.

Second life lesson: drink the small beer and be sure there’s enough lemon in your rum.

Pan pan, pan pan.

Many of you will recognize this as international radio language requesting assistance. It’s not a MAYDAY MAYDAY emergency, merely a need for a bit of support. I love producing this maritime blog, because I love researching the data. Okay, yes, I love digressing. But I’m not reaching a volume audience. Many have counseled me to stop dithering and do something progressive like allowing my blog to leap onto Substack, as well as WordPress. I believe in the educational importance of maritime heritage and know that it’s lost in a broken educational system. How might I multiply my audience? I believe that Dockwalloping is a good product, fun and occasionally controversial, why not expand? You know that I’m a dinosaur, an old-time navigator who used sextant and chronometer, and I honestly don’t want fancy electronics aboard. But I could warm up to a few thousand readers. Might some binary-wise reader suggest the steps I should take to increase subscription (still free) and readership? The inkfish would be grateful for the help.

Adkins

Leave a reply to howaboutnextweek Cancel reply