Dockwalloping #9

This is all your fault.

I set out to describe a delightfully grisly bit of sea lore: Why sailors called their daily ration of rum “Nelson’s Blood.” The well-circulated story suggests that when Admiral Nelson was killed during the Battle of Trafalgar his body was returned to England for a posh funeral. To preserve his body over the several weeks of transport to London, we’re told he was placed in a barrel (he was not a large man) filled with rum. On arrival – the story goes – the rum was missing! Obviously drained bit by bit from the barrel by thirsty sailors with straws.

It’s a grand (Guignol) story. Alas, it ain’t so. I have an obligation to history. Grudgingly I sought out the more pedestrian facts.

Horatio Nelson, one of eleven siblings, was sent to sea at the age of twelve to serve as a common jack. In time he was commissioned as a Midshipman and rose through the ranks (his family was wealthy and influential) to become a reliable, resourceful leader, achieving post captaincy fighting the French and Spanish in the Caribbean, the Atlantic, and the Mediterranean. He was small, about five feet, four inches, and well-spoken, known for his imaginative tactics, his courage, and (a rarity among commanders at the time) for seeing to the care and comfort of his sailors.

Nelson was not strong. Over his service he endured dozens of fevers and maladies, and he was often seasick. He was not lucky. He lost an eye and his right arm in sea battles. He married well but not happily and created an international scandal when he was smitten by and carried on an open relationship with a scarlet woman.

Emma Hart was the daughter of a blacksmith. In British society she could never be completely accepted. She was, however, a spectacular beauty. She used her looks with daring and flair, aligning herself with wealthy men as a hostess and mistress. A singer, actor, and a dancer who reportedly danced nude the length of a formal dinner party table, to applause. She became a model and muse to several prominent British painters, especially George Romney. Emma strategically balanced her liaisons with wealthy, powerful men to become a creator of fashions and a muse to the arts. Despite her downstairs birth, her grand parties and intimate salons became political pivots, allowing her to influence international relations. She married Sir George Hamilton, an older man, a British envoy posted to Naples. Thus she became, by courtesy, Lady Hamilton.

You can find an entire library shelf of bios and novels describing the lurid particulars of the Nelson/Hamilton scandal and her Upstairs, Downstairs connections. It seems obvious that the one-eyed, one-armed Nelson was a sitting duck when he met her at Hamilton’s home.

Less obvious is the effect Nelson had on Emma and even Sir George. At that time Nelson was the wonder boy of the Royal Navy, a brass-bound winner, producing surprising victories with daring tactics that occasionally ignored direct orders. Emma and her husband were completely conquered. The envoy passed possession of Emma to Nelson in a fog of admiration.

For years Nelson and Emma carried on flagrantly, happily, ignoring grumblings from Nelson’s British wife and the Nelson family. They produced a child, named Horatia, who was shuttled off in the care of prosperous families. They were together only occasionally since Nelson was largely at sea harrying Napoleon’s navy.

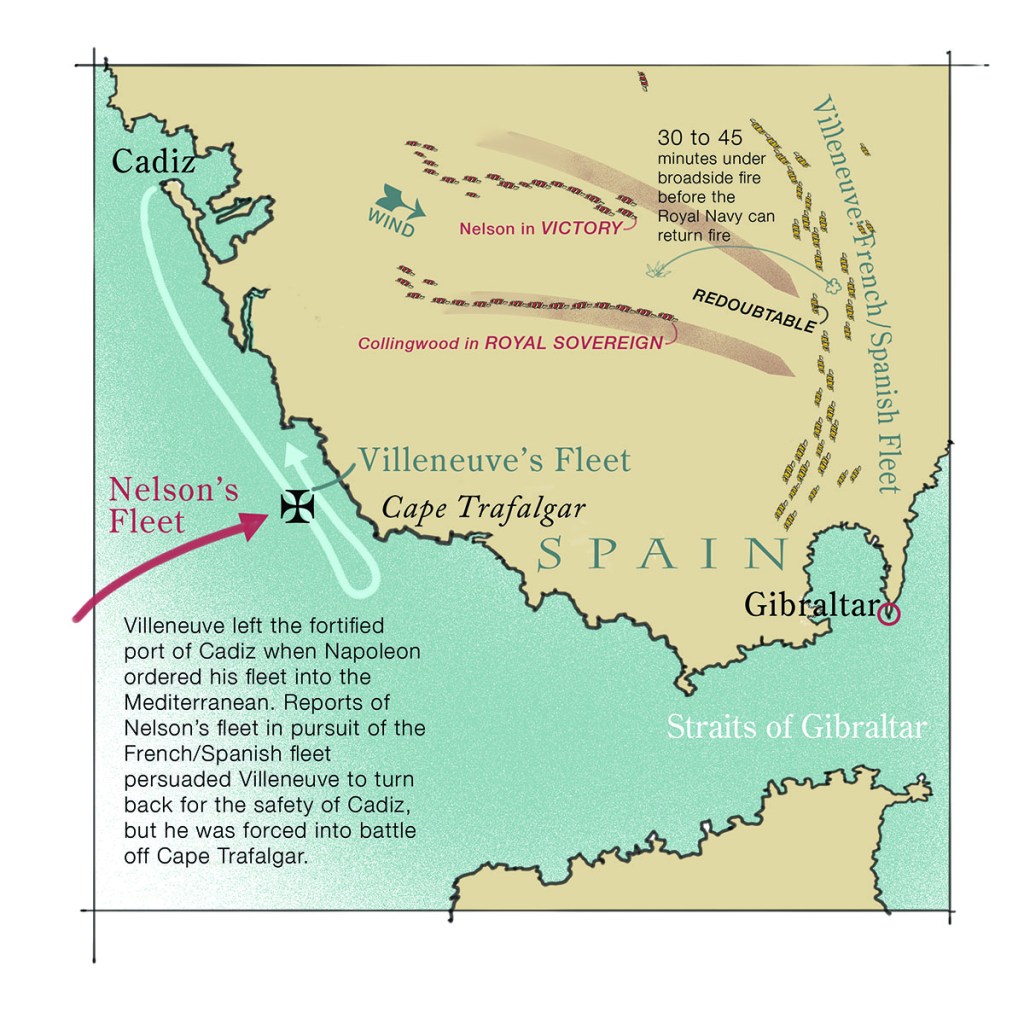

In March of 1805 a combined French and Spanish armada under Vice Admiral Villeneuve escaped the British blockade of Toulon during a storm, supposedly to attack British ports in the West Indies (the chain of islands from Florida to Venezuela, separating the Atlantic and Caribbean). Nelson sailed out of the Mediterranean in pursuit.

But Villeneuve’s crossing was a feint: Napoleon hoped to detain the Royal Navy across the Atlantic, waiting for an attack, while the Emperor’s ships returned quickly to France as protection for troop barges in a cross-channel land invasion of Britain.

Villeneuve was a hesitant commander. Landing at Martinique in the West Indies, he discovered Nelson’s squadron had arrived before him. Villeneuve turned back to Europe, reaching safety in the fortified port of Cadiz. Napoleon quickly ordered a new diversion to occupy the British: Villeneuve was to take the fleet into the Mediterranean, to support land maneuvers in Italy. Villeneuve complied reluctantly. Half way to the Straits of Gibraltar Villeneuve was warned that Nelson lay offshore with a strong British fleet. Again, the French Admiral reversed course, rushing for the safety of Cadiz.

On the 21st of October, 1805, the fleet of 33 French and Spanish men o’war moved north slowly in light airs, westerlies on their beams, making barely six knots. Nelson’s fleet broke the western horizon and approached with the wind from the west, Nelson in his flagship Victory.

The conventional battle plan would have been to close the distance, turn north parallel to the French/Spanish line, then hammer the engagement out broadside to broadside, but this was Nelson. “The Nelson Touch” was always subtle, unexpected, an unusual tactic with surprising advantages. Facing the combined French/Spanish fleet, Nelson was outgunned in weight of cannon-thrown metal. He had fewer and smaller ships. A broadside battle was always a risky proposition: chance loss of crucial rigging or spars here or there could destroy a fleet. At Trafalgar, Nelson refused the broadside maneuver and attacked in two columns straight ahead. Nelson in Victory meant to cross the enemy’s line about half way back behind Villeneuve’s leading ships,. His second-in-command, Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood in Royal Sovereign, attacked farther aft. Nelson managed to even the odds by closing and battling with only the trailing part of the enemy fleet. Villeneuve’s leading ships were cut off from the ships behind. They would take hours to turn about and sail south to the fight.

Clever strategy but this 90° line-ahead attack was a calculated risk: approaching the enemy fleet line-ahead meant that the British men o’war couldn’t fire their side-facing cannon. In light air they were forced to endure at least half an hour taking fire from the enemy’s long range broadsides before they could reply.

French and Spanish gunners did their best and managed hits among the British lines but the two-pronged attack closed the distance and broke the line. Following Nelson and Collingwood they crossed ahead and behind the enemy ships firing deadly raking volleys – fore-and-aft balls that tore through the length of the enemy ships, causing serious structural damage and decimating the crews.

Collingwood’s Royal Sovereign had a clean bottom (recently recoppered) and was the faster ship, so the southern prong broke the line first. In a short time British, Spanish, and French ships were blazing at each other in a confused melee, backing and filling their sails, attempting to board and carry vessels. Several times Victory was about to be boarded by superior forces but passing British ships swept the enemy decks clear of boarders with grapeshot and cannister. (A grapeshot is about the size of a walnut, packed in loosely connected “stands” of 9 balls. Cannister is a light can filled with a few hundred musket balls that bursts when it’s fired. Both are vicious anti-personnel rounds.) It’s not worth describing the noise, smoke, motion, and confusion in that hellish stretch of water.

Nelson’s flagship, Victory had engaged the French Redoubtable so closely that the big ships were locked together, turning around each other. Imperturbably Nelson walked the quarterdeck with his friend and the flagship’s captain, Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy. At about 1:15 a musket ball fired by a French marine high in Redoubtable’s rigging – an easy shot, no more than 15 yards – entered Nelson’s upper left shoulder just forward of the joint, broke a rib, punctured a lung, severed his spine, and lodged inside his right shoulder blade, a fatal wound. He was carried below but stopped his bearers to offer advice to a midshipman handling the ship’s steering.

Everyone not actively engaged rushed down to the cockpit (not a racing boat’s helm cockpit but the lower-deck protected area where the ship’s surgeon worked) to be near Nelson. A famous painting of Nelson’s death by Arthur William Devis (who was aboard at Trafalgar) shows about twenty figures around him. We doubt there were that many but they all wanted their face in the picture. At one point he famously said to his friend, “Kiss me, Hardy, I’m dying.” Men kissed each other in that era, nothing slobbery but ceremoniously, for brotherhood and emotion. He also asked that his friends and his nation care for Lady Hamilton and Horatia. Nelson lapsed into unconsciousness and died about an hour later.

The Battle of Trafalgar was fought furiously for four and a half hours. It was an enormous strategic success, setting Napoleon back on his heels. Villeneuve’s fleet lost 22 vessels. Only one was sunk: fire invaded the magazine of the French Achille, and she exploded. Only 11 of Villeneuve’s fleet straggled into Cadiz.

The Napoleonic War was fought with loud propaganda, persuading war-weary citizens on both sides that a little more effort would turn the tide. Nelson was already a darling of the press, so it was apparent that his body should be conveyed home for a pomp and ceremony funeral.

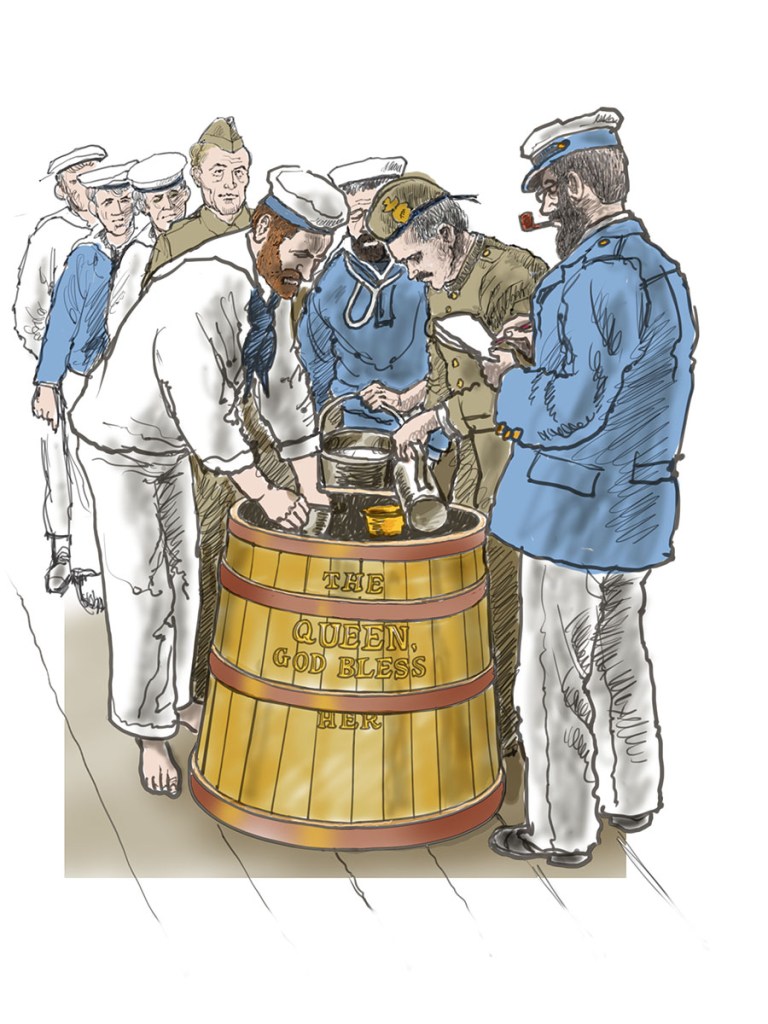

Aboard Victory Nelson was barreled, yes. The ship’s doctor did not preserve Admiral Nelson in rum but in a mixture of strong brandy, camphor, and myrrh (a funeral spice familiar to the Magi at Jesus’ birth). Probably undrinkable. Feh. The barrel was lashed to the Victory’s mainmast under 24 hour guard. The flagship was so mauled in the battle that it had to be towed to Gibraltar for major repairs. A fast sloop, HMS Pickle (spare us the pun), was sent with news of the victory and Nelson’s death to London. In Gibraltar Nelson’s body was replaced in a lead coffin filled with spirits of wine (what we would call alcohol).

Nelson was given a fabulous state funeral with a black barge bearing his coffin pulling upriver from Greenwich, landing beside the Tower of London, thence to St. Paul’s Cathedral where he was entombed in a crypt originally planned for Henry VIII (Henry’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, had other plans for his burial and, after all, Henry’s lead coffin exploded, a yarn for another time.)

[You may read a tolerably accurate account of the barge and funeral in C. S. Forester’s Hornblower and the Atropos, one of the fictional Horatio Hornblower tales.]

Lady Hamilton was not permitted to attend the funeral. Nelson’s friends and his nation did not treat Hamilton and Horatia well. Emma died deeply in debt, of drink and laudanum, in 1815 at the age of 49.

You may see Nelson’s crypt at St. Paul’s, and you may see his uniform with the musket ball entry at the Greenwich Museum. You may visit Trafalgar square and view Nelson from a distance atop the Nelson Column. Several of these columns occur across Britain but the most contested column was in Dublin, where British heroes have less currency. In 1966 a few of the lads blew the column with a hefty charge of gelignite. Here is a URL for the “commemorative” song about the deconstruction.

Leave a reply to charlescoull Cancel reply