Dockwalloping #8

Have you ever begun a project with a light, untroubled heart – “This will be a lark, no sweat.” – but a bit farther down the road you discover that you’ve navigated yourself into a swamp and the sun is dropping low?

The usual subject of this blog is maritime heritage, which is a big chunk of our culture overlooked by landlubber historians. The blog’s special focus is usually “sailor talk on the dock,” how maritime language lodged itself essentially in our common tongue. With a light heart I meant to explain that “little nippers” were children aboard sailing vessels who played a crucial part in heavy hauling. Simplicity itself.

Then, looking seriously at the task and calculating the hauling force needed at a time when human strength was the only applicable motive power, it was not clear how that strength could be multiplied. Reviewing plans, models, paintings, and details of navy and merchant ships in the pre-steam Age of Sail, there are no obvious solutions, and only spotty clues. Was Erich von Däniken really right? Was weighing anchor the work of ancient UFO aliens?

No magic, no UFOs. We’re obliged to fall back on a wise historical principle: The old guys were not dummies. After rummaging through bits and pieces of ship narrative and fragments of shipbuilding plans, the process of producing enormous hauling power came into focus. My much simplified sketch below of a ship retrieving her anchor is new to me. There may be others, and we hope they’re more accurate, more comprehensive, but I haven’t found them.

Consider the problem: a ship is being held by an anchor buried in the sea bottom. Let’s hypothesize a small Royal Navy frigate like Jack Aubrey’s Surprise. Its primary wrought iron anchor weighs between two and three tons. It’s connected to the ship by, conservatively, 150 feet of hempen hawser 10” in diameter. To the weight of the anchor and rode (length of anchor line), add wind resistance: the lightest breeze on the apple-cheeked bow of the ship, the masts and yards, and the mile or two of controlling cordage above it contribute a considerable force.

The heavy hawser must be hauled up through the hawse hole [A] 10 or 15 feet above the surface. Taking up the rode is overcoming wind resistance until the ship is over the anchor. Then the ship must exert enough force to dislodge the multi-ton anchor deeply set in six to ten feet of dense sand, silt, and cobble. As the hawser is drawn aboard it must be snaked down from the open deck through two or three lower decks and into the cable tier below the waterline, coiled into multiple loose coils six or eight feet across [B] (rolling up 10” hawser is like putting an anaconda to bed). When the anchor is atrip just below the bow (“thick and dry for weighing”) it must be lifted above the surface, detached from the hawser, and hung to port or starboard on the catheads [C], then lashed securely outside the bow.

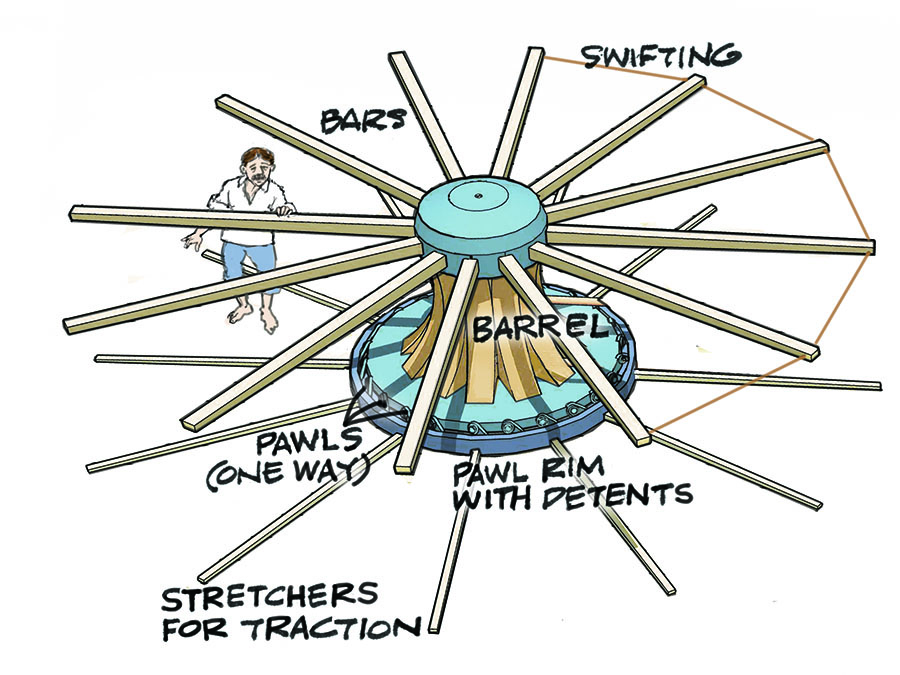

The tool for the job is a capstan [D], a big winch as tall as a man. Set into the cast iron crown of the capstan are eight to twelve sockets that receive capstan bars of ash or oak [E]. When they’re socketed, they’re pinned – secured in place by a metal pin, and swifted – their outer ends are notched or drilled to hold a taut swift line that draws inward and sets the bar-ends evenly and rigidly. The bars are seven to nine foot levers. At least three sailors can strain at each bar. On the deck are laths fixed like dinghy stretchers that make purchases for feet walking around the capstans [F]. The relatively slim barrel of the capstan and the long levers of the bars provide prodigious mechanical advantage. This advantage is secured by angled iron pawls [G] swung from the base of capstan, engaged in the iron detents of the pawl rim [H] below. Even a minor turn in the capstan (in the hauling direction) will be announced by the iron pawls clicking into new one-way detents; the hauling line can be eased but the capstan can’t go backwards.

12 bars, 3 men per bar (for simplicity I’ve shown only one per bar), 36 burly sailors using their whole bodies to walk the capstan around. Now add another 36 sailors, because a duplicate capstan fixed to the same “axle” spindle is operating one deck below, twice the power.

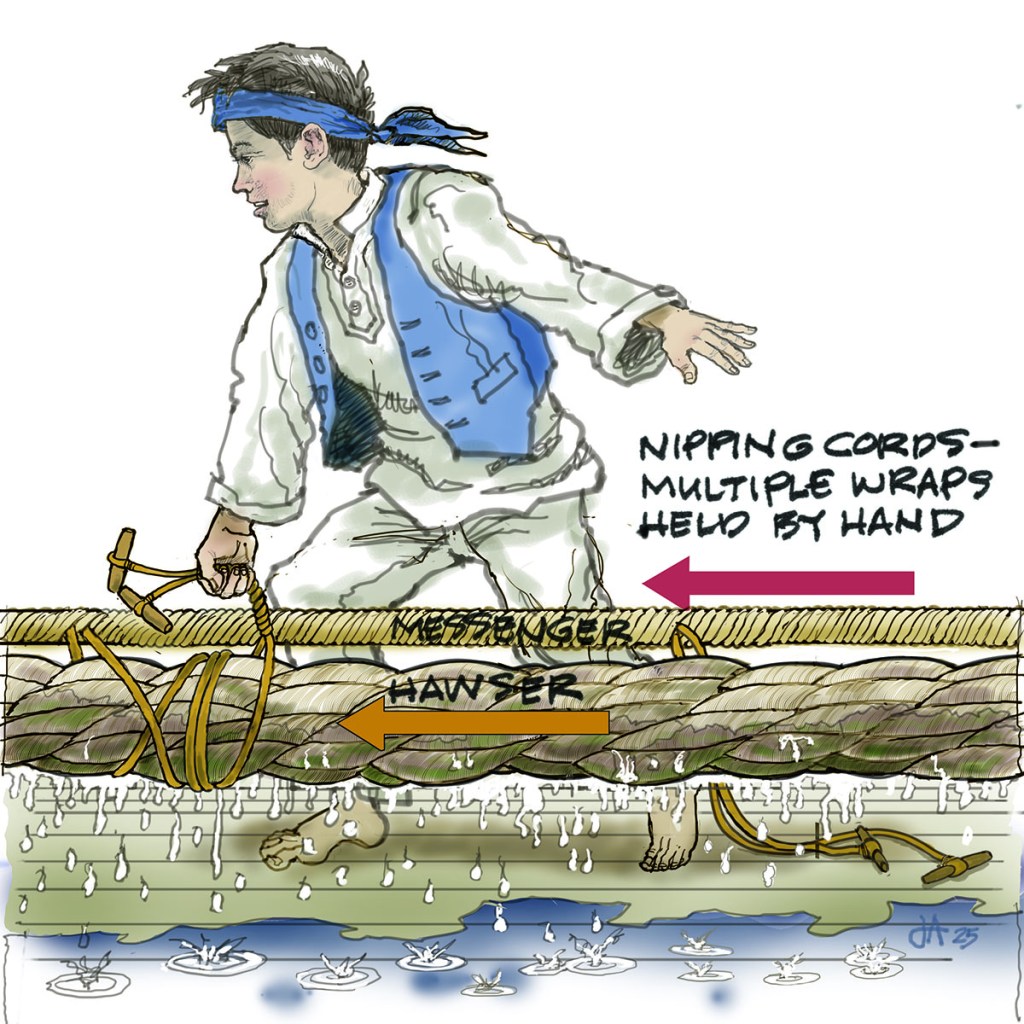

On the upper deck a 10” hawser won’t wrap around the capstan barrel; it’s too thick, stiff, it won’t bend enough. Solution: the messenger [I], a strong but thinner line wrapped several times around the capstan’s barrel., The messenger is spliced as an endless loop that runs forward from the capstan barrel to a turning block and back to the capstan. Every few feet a pair of light cords [J] are spliced into the messenger.

Small, nimble ship’s boys wrap the messenger’s cords a few times around the big hawser. They twist the cords against the hawser in a simple lock [K], and hold them in place by hand. When the capstan is turned the messenger runs from the forward turning block, taking a length of the big hawser with it. The kids who nip the hawser to the messenger with the cords – the little nippers – move with messenger and hawser toward the capstan. When the hawser nears the capstan, the nipper nearest the capstan releases his cords and runs back to the turning block to take a new nip. The hawser is fed down through the decks [L] to the cable tier where sailors, filthy from the slime and mud on the hawser, coil the awkward anchor cable.

You may notice a fiddler sitting on the cap of the capstan [M]. Another instrument might be the high-pitched fife. A bit of music surely picked up sailor spirits but the music had a practical purpose: applying great human force works best in rhythmic patterns of effort, and music times those efforts so the sailors’ power is exerted at the same instant. Random pull is wasted. When these sailors are asked to hoist a yard or to tighten a sail’s sheet, they’ll do it in rhythmic pulls to a work song, a shantie, the subject of another posting.

Now we’ve explained the sea-term “little nippers.” We can see a playground full of gamboling kids and say, “Look at the darlin’ little nippers.”

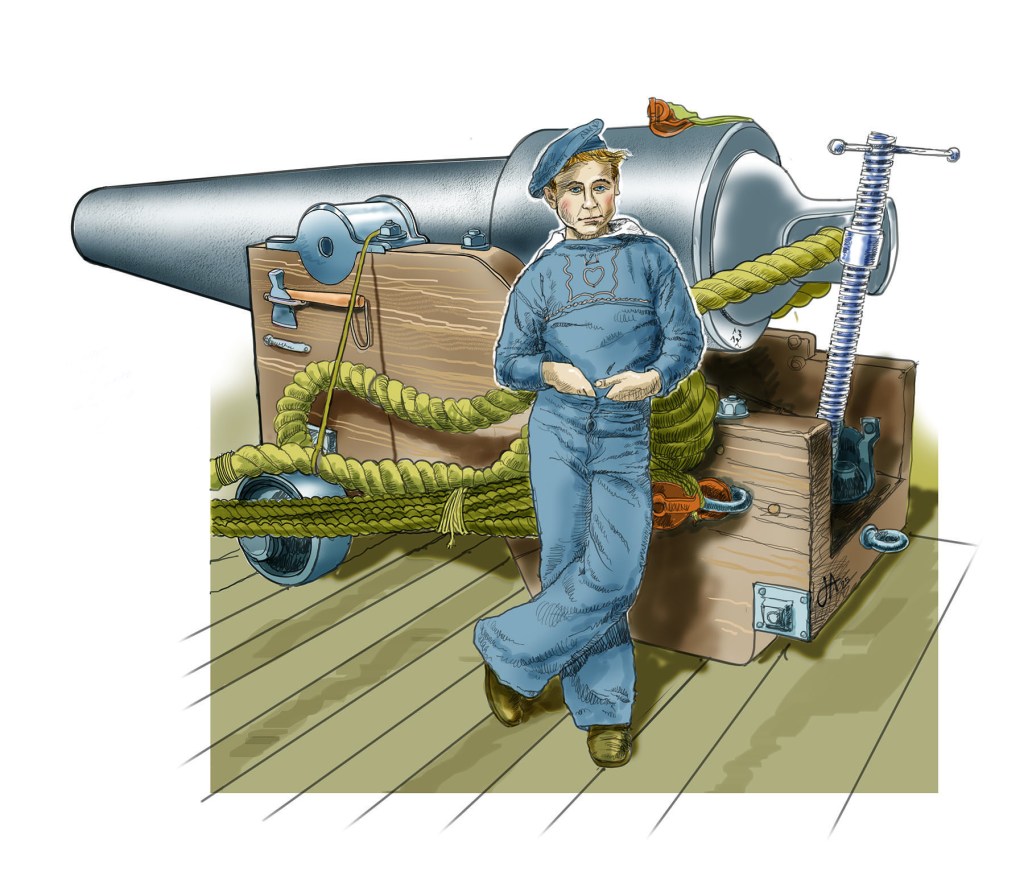

The original nippers weren’t playing but working hard at the crucial hauling function. In battle these children were powder boys who ran between gun deck and the magazine. Below the waterline they received gunpowder charges measured into fabric bags from the gunner’s mate. How did they see in the deep, dark magazine? Not with a naked flame! A small lamp room built by the best cabinetmakers and caulked with more care than the hull had a window into the magazine for light. Carrying the deadly charges in leather buckets the powder boys pushed through the slotted, water-soaked fear-naught screen that prevented any floating spark from blowing up the entire ship in a flash. Then the boys ran up several companionways to the deck and to their assigned gun. Back and forth as long as the guns spoke.

The presence of these children aboard naval and merchant ships is a kind of surprise. We’ve all heard of “cabin boys” and perhaps even “powder monkeys” but they don’t register as a group. Children are seldom, if ever, mentioned in accounts of battles or in descriptions of shipboard life. Yet aboard the hypothetical Surprise frigate, or a comparable merchant ship, it’s likely there would be 20 to 40 boys in a crew of 200 to 250 men. With this gang of children we’re confronted with a new complexion of life at sea! Where did they come from? Who determined that children as young as 6 or 7 could be useful mid-ocean? How were they treated? Did they have a childhood?

Hindsight is not 20/20. Considering these children from our jaded 21st century acquaintance with children and parenting is not useful. A child in any but “noble” families was expected to be useful, productive, even profitable as soon as he or she could parse whole sentences. In Europe or America a rural farming or dairy family depended on their children to manage light but important jobs for a full day, as long as fathers and mothers worked. It was undoubtedly exhausting work and at day’s end the family’s four or five working children collapsed into the same bed. It wasn’t harsh; it was life.

In some bleak ways children were dispensable. In the 18th and 19th century principles of disease were mediaeval, the medical practice of most doctors was wrongheaded, health was at best a mystery. Childhood diseases like measles and chicken pox were more virulent, then, and about a third of all children died in their first year. Only about 43% reached the age of 5. At age 10, a child had a little better than a 50/50 chance of reaching adulthood.

In cities families hired out their children to work for weavers, tanners, butchers, manufacturers. The mortality rate in crowded, filthy, sewage-stinking cities was brutal for children and adults. On the subject of ships boys one observer suggested that the ships might be manned by orphans alone.

Not much study is focused on children at sea. Perhaps the most practical perspective is the unfamiliar concept of children as a burden unless they could contribute to the family’s survival, working the fields, bringing in wages, apprenticing to trades. Sending a child to sea was in some ways a gift: a little nipper would be learning a trade, bringing back wages, would be fed and clothed and cared for as a part of the crew with some present value and as a prospective sailorman.

Was a child’s life at sea better than a life ashore? Impossible question. In some ways ship life was more regular and – beyond infrequent battles – no more dangerous than working in coal mines. The ships boys were well fed (awful food, another blog) but subject to diseases inherent in living closely with 200 men without showers or safe water (beer and rum grog were less toxic). The familiar percentages of death among Royal Navy sailors: 10% died in battles; 90% of deaths were due to shipboard sickness.

This is not well documented territory and should receive creative analysis as well as historical and statistical academic study. A few revisionist LGBTQ+ historians are eager to assume that pederasty was a factor in recruiting ships boys; this is doubtful, given the stigma of such abuse in most historical eras. In the Royal Navy the punishment for “unnatural acts” was unequivocally death. Open berthing on the gun decks for hundreds of men extinguished any notion of privacy; it was a promiscuous life but rigid in its mores.

On navy vessels petty officers and skill ratings like coopers, gunners, blacksmiths, carpenters and cooks sometimes brought their wives with them. On merchant ships and long-voyage Indiamen (“company” ships) women were even more familiar members of the crew. Seagoing women might have softened the lot of the smallest children. Indeed, child care for the youngest was part of a ship woman’s duties. They minded the youngest boys and perhaps taught them in some rudimentary way.

The reality of children aboardship is not in doubt. We know something about the attitude of officers to young men of wealthy or noble families who sent their sons to sea as midshipmen, apprentice officers as young as 8 or 9. The conditions for common ships boys is undocumented.

A blog like this is not one-sided: your analysis and speculation can be valuable to a discussion and could be a springboard to serious academic inquiry. Talk back, react, opine. Think carefully about this unknown, trying to dismiss 21st century attitudes, avoiding cliché assumptions, and make this a forum topic that can begin a real study. Your shipmates will be listening.

Your comment, dissent, data, and support are welcome