Sailor Talk on the Dock #7

JACK TAR was and is a general moniker for sailors, especially in the Age of Sail. What was so tarry about Jack?

Jack lived in a world of tar. The barkie, itself, was waterproofed by caulking every plank seam with fiber dipped in tar, called oakum. Every item of deck furniture – hatch coamings, doghouses with glass windows to shed light on the officers’ mess table, companionways, anything raised above the level of the out-sloping deck– was set firmly into hot tar to seal it against leaks.

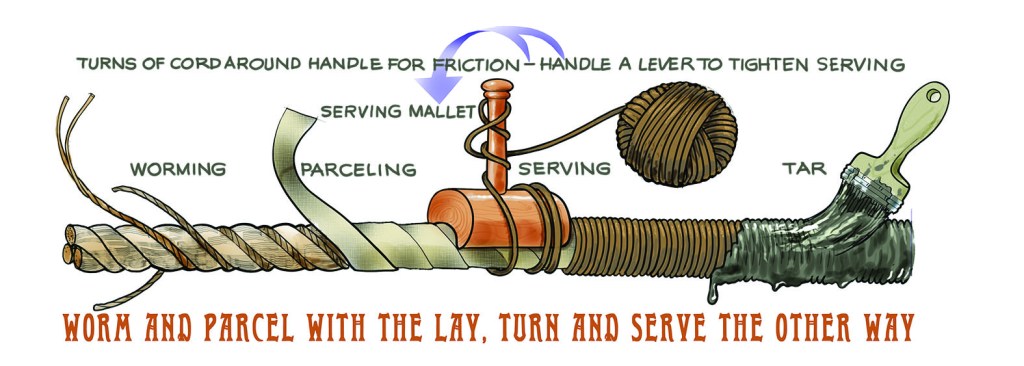

Above Jack, miles of cordage held the masts in place and commanded the sails to assume their duties in a web of tension. The cordage was provided by Mr. Natural: all of it was organic vegetable fiber exposed to the elements, night and day, subject to as much rot as a sandwich left on deck. Many fibers were used but most were hemp cousins, tough and unyielding but vulnerable. Running rigging, cordage that controlled sails and yards and adjusted trim, required maximum flexibility to run back and forth through blocks and deadeyes. These active lines were left natural. The most vulnerable cordage was the standing rigging, the shrouds and stays that held and stiffened the masts, thwartships and fore-and-aft, in their several vertical parts. These comprised the stability of the rig and were protected elaborately.

Two strand light line dosed with tar and turps (marline) was laid spirally between the three strands of heavy cordage along the cunt line (all levity aside, this is the technical term for the cusp between rope strands). The marline filled the gap and “rounded” the cordage cross-section. Now for levity, this is called worming and it follows the lay (spiral direction) of the cordage. Next, spirals of (old) sailcloth are wrapped around the “rounded” rope-and-marline in the same direction, with the lay. This is called parceling. Now similar marline is served – tightly wrapped around the wormed, parceled cordage in the opposite direction. Shellbacks have a chant mnemonic to remind young shipmates: Worm and parcel with the lay, / Turn and serve the other way. Finally this cordage mummification is sealed by coating it with black tar, protecting it against weather minutely.

What, indeed, is tar?

I wish I hadn’t asked myself that question because it summons chemists, engineers, Big Oil, and punctilious historians to argue about the proper industry term for black, sticky stuff as a derivative of petroleum sources, properly called bitumen, and black, sticky stuff winkled out of coal, peat, or wood by heat, properly called pitch. Asphaltum is another name for bitumen and is associated with road paving, as in asphalt, tarmac, or macadam (this last by association with an industrious British contractor). One of the earliest words for bitumen is mummiya, an Egyptian term for bitumen with which Late Kingdom, Ptolemaic, and Roman era Egyptians covered their reverently wrapped bodies, hence our term “mummy.” Let us quietly push off from the dock and semantic argument by accepting the almost universal descriptive term: tar.

Tar is a black, sticky hydrocarbon complex. For centuries, the best marine grade tar came from Sweden and Finland, where it was produced as a cottage industry at the edge of pine forests. Lengths of pine heartwood about finger width were stacked snugly in a stone pit. The pit was tightly sealed using moss and turf. A great fire was built over the pit’s cover and lit to burn for days. The heart pine “burned” with almost no oxygen. The resins that make up the pine were released by the heat and ran along the inside of the rock pit wall to a central hole over a stone passage, thence to a pot collecting hot liquid tar. At the end of the burn, the tar had been captured and the pit contained valuable pine charcoal for blacksmiths’ forges. Tar was for centuries a primary export of Sweden and was called Stockholm tar.

We must shove our oar in, now, to insist that the United States produced prodigious amounts of fine tar. Pines up and down the East Coast produced the valuable trade commodity. Southern states’ pine forests additionally tapped their long leaf yellow pines like maple trees for their resins, which were distilled into indispensable turpentine, a superior solvent for paint and tar, itself.

In a few places on the globe, tar simply appears, bubbling up from the earthen depths. A famous tar seep is in downtown Los Angeles, the La Brea Tarpits. (Sorry to interrupt but it’s really bitumen.) Tar seeps are deep fissures in the earth sending up geologically ancient sea floor goo processed by magmatic heat. The astounding thing about La Brea is the thousands of ancient animals large and small that got stuck in the sticky mess over many thousands of years and died, eternally preserved by the nasty stuff. If you’re short on nightmares, Google La Brea’s dire wolves.

The largest tar seep is in the Caribbean on Trinidad, a tar lake of about a hundred acres, 250 feet deep, containing about 10 million tons of tar (bitumen!). That glorious seadog Sir Francis Drake reported the Trinidad tar lake to Queen Elizabeth I when he returned from his circumnavigation.

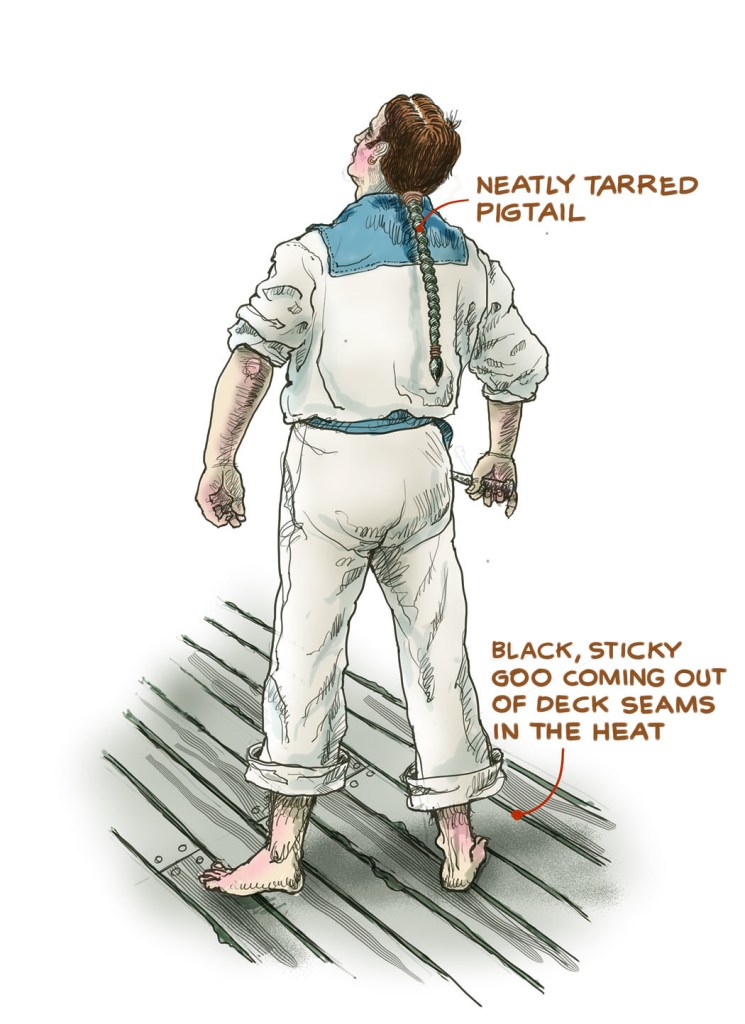

Black, gooey, interesting, and a big part of Jack Tar’s world. Close on, it was not unusual for traditional sailormen who took pride in their long pigtails to stabilize them (and perhaps plait in an extra inch or two from the ship’s barber) by soaking them in a mixture and tar and turpentine. Neat and bug free.

Tar has distinct medicinal qualities, being a germicidal and, in dilute form a valid treatment for some skin rashes. Pots of tar were burned to discourage mosquitoes. The Finns swore by tar as their best medicine, saying “if sauna, vodka and tar won’t help, the disease is fatal.” Some ship’s surgeons treated amputations quickly by dipping the stump of a leg or arm directly into a hot pot of tar.

A century and more before the Dixie Cup U.S. Navy sailorman’s cap, a blue water man might wear a hand-plaited “straw” hat he had run up himself off watch, using fiber from a liberty port – wheat straw, raffia, palm leaves, dried seagrass. He might also score a fur felt hat from a shore chandlery. Straw or felt, he likely coated it in tar.

Why? At least half of ship’s complication is above the deck, and every hour of the day the topmen are making more sail, reducing sail or even bunting up an entire mainsail or foresail. All those shipmates above you, all that activity, somebody’s going to drop something. A stiff tarred hat keeps the sun off but it’s also a forerunner of the jobsite hard hat that could save your noggin.

In driving rain and stinging spray, something between you and the wet must have been a comfort. Sailormen (in the Age of Sail there were virtually no sailorpersons) often ran up a light canvas parka waterproofed with tar and turpentine. It was an obvious extension of the tar-waterproofed canvas sheets laid over the latticework hatches. These protective treated sheets were called tarpaulins (tar + Olde English pallen, “heavy cloth”), and the name is sometimes applied to sailors, themselves, as in “a shore party of tarpaulins.”

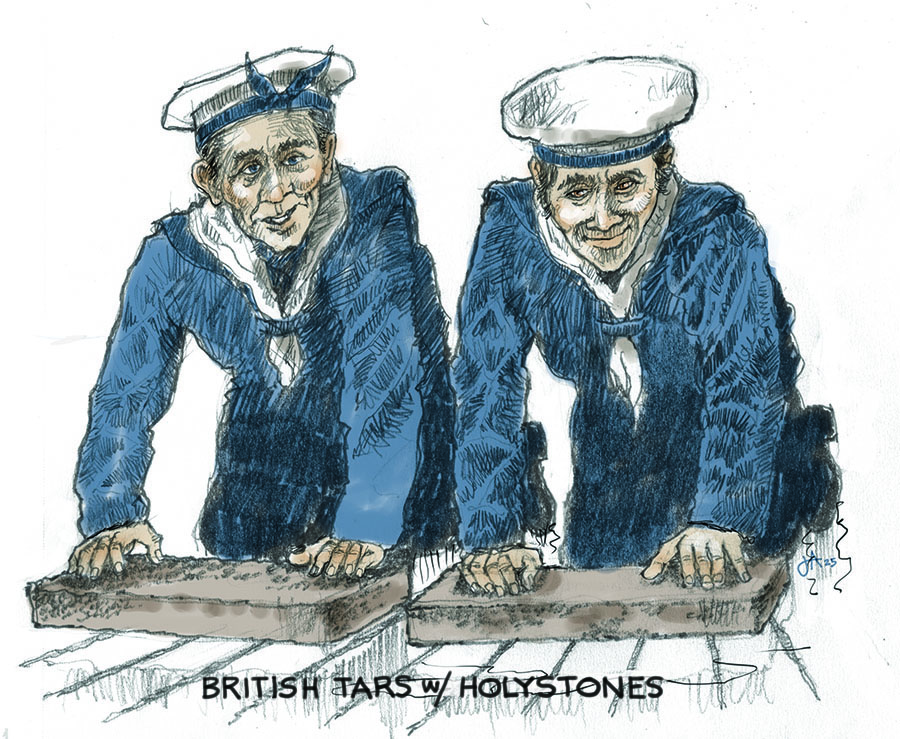

Our own age is graced with hundreds of synthetic sealants and treatments that take the place of black, sticky goo. Many professions – roofers, stockmen, veterinarians, road builders – still use tar. Sailors not so much. Tar is a curse, soiling everything it touches. If you work near tar you will get dirty. Ask the Royal Navy mateys who scrubbed the oaken decks. In warm weather, tar dripped from preserved blocks, and strops, bubbled up out of deck seams, and fell from tarred rigging along with the reclaimed cooking fat (slush) used to grease masts against mast-binding. Tar and the Royal Navy’s fetish for clean-deck order obliged dozens of shipmates to work on their knees first thing in the morning watch, bent over heavy sandstone blocks in a rhythmic nodding not unlike prayer (hence, the blocks were called “holystones”), using blocks, sand, and seawater to physically grind away black, sticky goo. Jack Tar lived in a world of tar.

I love pursuing the subjects for this blog. I mean to post about once a week but I’m a lenient editor: I let myself keep researching and illustrating beyond the sensible limit a profit-driven editor might allow. This Tar blog took four more days than I had scheduled. A professional needs deadlines and good editors, limits that brace writing and illustration into disciplined purpose. But I’m going to make an assumption: if a subject fascinates me beyond normal limits, I’ll assume that you could be amused, as well, and I’ll continue to dive deep and take time. I hope it’s worth your time. Please suggest blog subjects you might like to read about. And please suggest subscribing to your friends and colleagues.

Adkins

Your comment, dissent, data, and support are welcome