YOU CAN’T BEAT A DEAD HORSE. This self-evident factoid sounds terrestrial, because time-honored lore insists that sailors and horses are not easy companions. A pigtailed sailor up on an English saddle riding to hounds is a comical figure, though Captain Jack Aubrey of O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin series would tell us to belay our levity (and add that we were Dutch-built butterbox buggers). It is to larf: dead horses were a lively interest to sailors.

In keeping with the immemorial custom of the sea, sailors were often paid a month’s wages before shipping out, so they could settle local accounts, see to a family’s needs, or invest with women of negotiable virtue. At sea, sailors reckoned that their first month’s salary was already spent, so they were working for nothing. Jack Tar was never attentive to mathematical niceties.

This “work for nothing” was considered paying for a dead horse. During this first month when mates found a new crew reluctant to obey strenuous orders or leap into the rigging, lively-like, the officers’ bellowed exhortations were considered beating a dead horse.

One happy shipboard occasion was the end of the dead-horse month, when the jolly tars would be working for themselves, again. (Note math deficits, above.) On that lucky day, sailors cobbled up a horse from scraps of canvas and wood, stuffed with straw from sheep and pig mangers, and threw the dead horse overboard! Free at last!

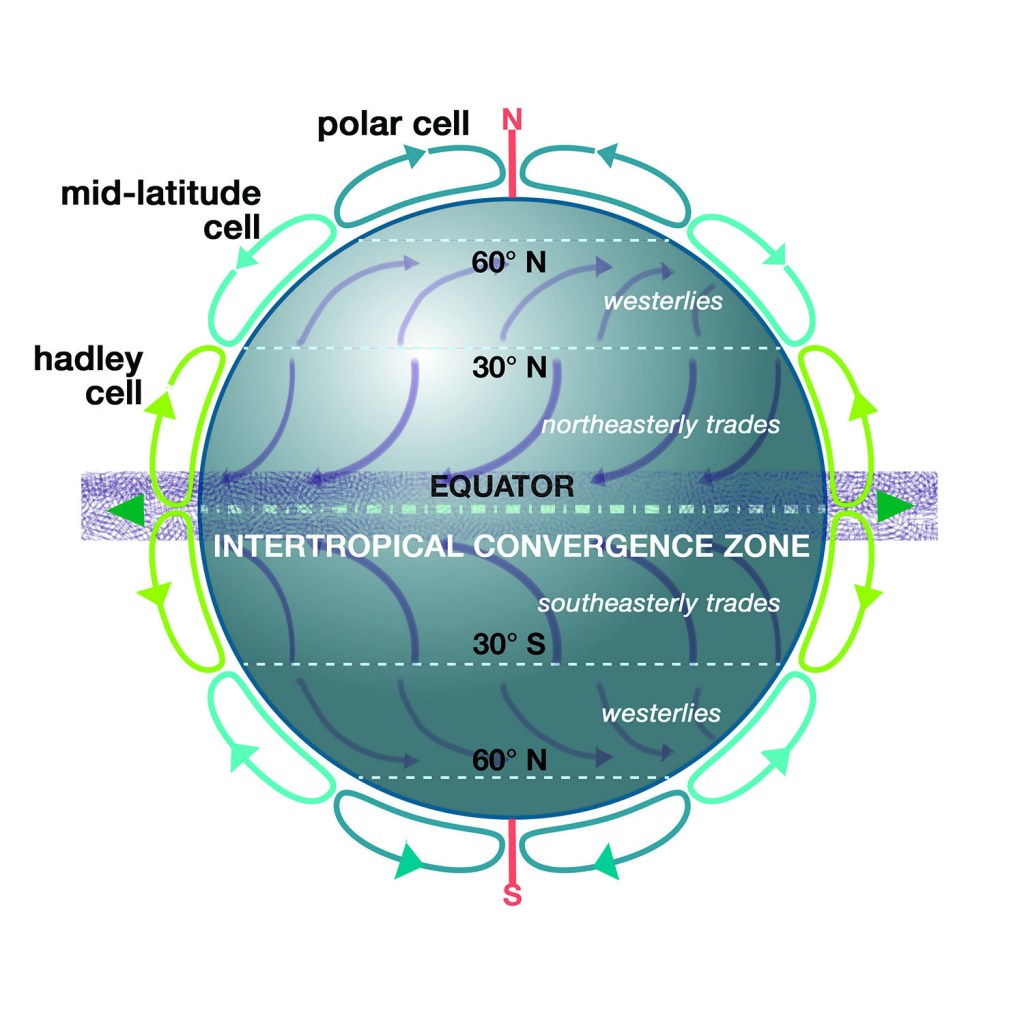

We sail on to a grislier reality: the horse latitudes. Almost as grisly, we fetch up against the physics of convective currents arranged around the earth like turning bands: cold air falls and warmer air rises, and the surface winds that are generated by these vertical drivers arrange themselves in three ranks, from the equator to the poles. They’re called cells, and each has a designation: polar, mid-latitude, and Hadley cells. Think three dimensionally of these rolls of air moving up and down – and laterally, due to Coriolis and other global forces. These lateral surface movements are our trade winds, that can change locally and weekly but may be trusted seasonally.

But what about the horses?

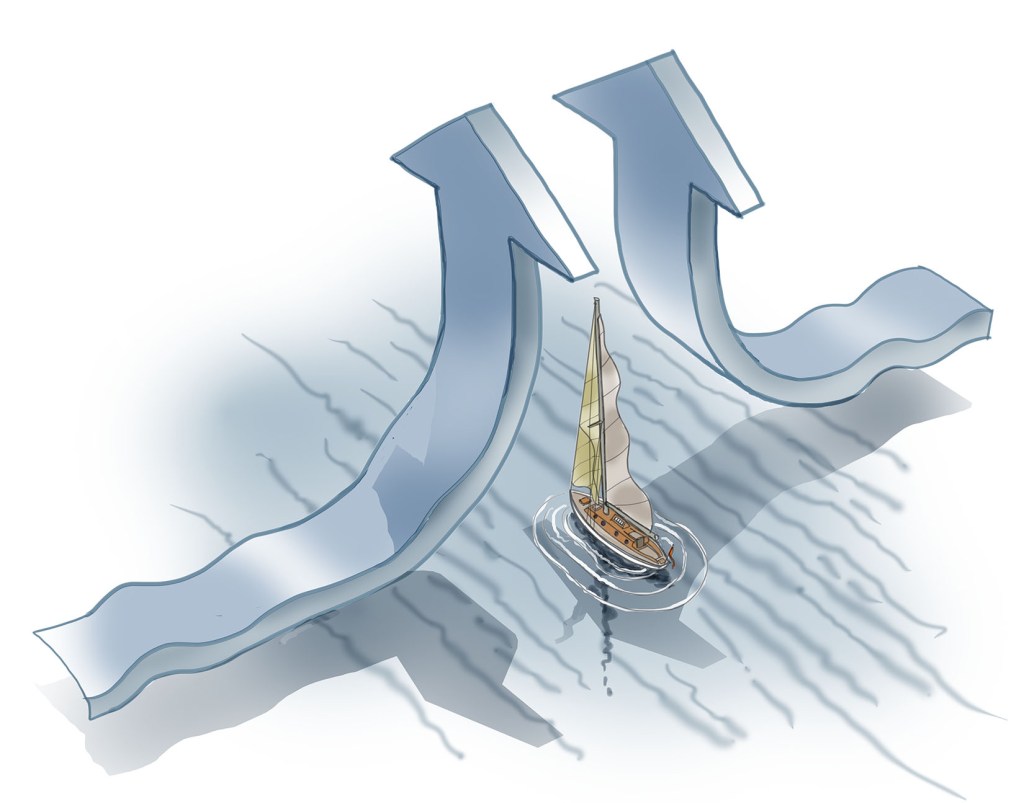

Consider the north and south Hadley cells sweeping toward the equator. These enormous volumes of air meet and rise. In the cusp between the north and south cells, the converging air, rising, creates a troublesome band of calms without regular winds. A vessel heading between the northern and southern hemispheres must cross this frequently windless barrier and may drift without a breeze for days, weeks. This intertropical convergence area is called the doldrums. In the age of sail, waiting for a breeze to propel your vessel to reliable trade winds could be an unpleasant trial.

European merchantmen bound for the New World often carried cattle and horses. If a ship was becalmed for a time in the equatorial heat, the supply of water (a crucial concern for any captain) ran low. Water for the crew was far more important than water for livestock. It was not uncommon in extremes to push the horses overboard. Floating horse bodies were not uncommon sights in the doldrums, hence, the horse latitudes.

A few adventurous lexicographers have ginned up other origins for the term, but none are so simple and practically understandable. Perhaps sailors and horses are, indeed, uncomfortable partners: thirsty sailors were happy to see them go.

Illustrations by Jan Adkins for Dockwalloping, ©2025

Your comment, dissent, data, and support are welcome